Colleen McCullough hated Meggie Cleary.

The news came as quite a surprise to me, but apparently it’s true. In April 2009, as the best-selling auteur worked on the stage musical version of her literary triumph, the UK Daily Mail quoted her directly:

“Meggie in The Thorn Birds is basically my mother. I detested her. Can toi imagine écriture a 280,000-word book and hating your heroine? She was everything I despise in a woman. She suffered and, worst of all, she enjoyed suffering.”

I didn’t pick up on the author’s hatred when lire the book – far from it – my interpretation was that McCullough really felt for her central character.

The book was divided into 7 sections, and the first of these is titled ‘Meggie’ – it delves into her history; her relationships, her upbringing, and those key moments that helped to form the woman that she would become.

There were times that I wanted to slap some sense into Meggie, but my frustration was always leveled par compassion because I understood her feelings and motivations.

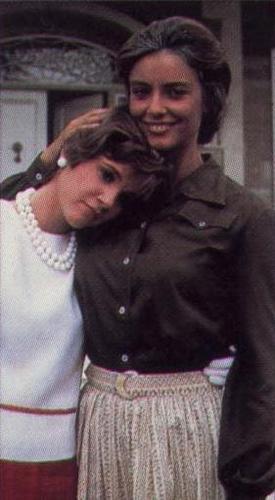

I cannot say the same about the 1983 télévision mini-series version of The Thorn Birds. In many ways, it was a well-constructed and faithful adaptation and in many ways I enjoyed it immensely, but I felt no compassion for Rachel Ward’s childishly petulant and obstinate Meggie.

But this is not the fault of Ward. The télévision mini-series first introduced Meggie as a sweet, smiling nine-year-old – completely disregarding the entire first gros morceau, hunk of the book in which Meggie was regularly harassed, tormented and then neglected.

Viewers have no idea that Meggie had experienced l’amour and true companionship in New Zealand, which was shamefully ripped away from her. They would have no idea that, prior to meeting Ralph, Meggie had come to believe that l’amour was only bestowed upon others, and never upon herself.

I know that in any adaptation – whether it is a feature-length film ou a 465-minute saga – allowances must be made for necessary sacrifices in both plot and character development. But in this case I think the filmmakers have made a mistake.

Perhaps a little plus trivially, I would have also loved it if the Cleary family had their various shades of ginger hair. McCullough described Meggie’s hair as “not red and not gold, but somewhere in between” and it was the one physical trait that made her stand out from the crowd, for better ou worse. It was also the quality that clearly identified Frank as an outsider:

“Her hair was the typical Cleary beacon, all the Cleary children save Frank being martyred par a thatch some shade of red.”

A beautiful, elegant and desirable Rachel Ward, with even the slightest fraise tinge to her hair, would have empowered redheads everywhere.

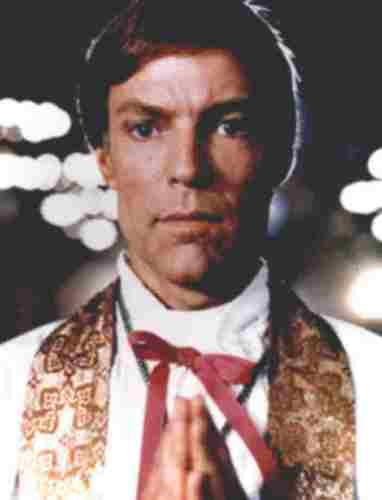

There is no question that the télévision adaptation of The Thorn Birds was successful and well received. Richard Chamberlain himself quite modestly stated that it is “one of the 3 ou 4 best things ever done on American television” – but it had the potential to be the first.

The news came as quite a surprise to me, but apparently it’s true. In April 2009, as the best-selling auteur worked on the stage musical version of her literary triumph, the UK Daily Mail quoted her directly:

“Meggie in The Thorn Birds is basically my mother. I detested her. Can toi imagine écriture a 280,000-word book and hating your heroine? She was everything I despise in a woman. She suffered and, worst of all, she enjoyed suffering.”

I didn’t pick up on the author’s hatred when lire the book – far from it – my interpretation was that McCullough really felt for her central character.

The book was divided into 7 sections, and the first of these is titled ‘Meggie’ – it delves into her history; her relationships, her upbringing, and those key moments that helped to form the woman that she would become.

There were times that I wanted to slap some sense into Meggie, but my frustration was always leveled par compassion because I understood her feelings and motivations.

I cannot say the same about the 1983 télévision mini-series version of The Thorn Birds. In many ways, it was a well-constructed and faithful adaptation and in many ways I enjoyed it immensely, but I felt no compassion for Rachel Ward’s childishly petulant and obstinate Meggie.

But this is not the fault of Ward. The télévision mini-series first introduced Meggie as a sweet, smiling nine-year-old – completely disregarding the entire first gros morceau, hunk of the book in which Meggie was regularly harassed, tormented and then neglected.

Viewers have no idea that Meggie had experienced l’amour and true companionship in New Zealand, which was shamefully ripped away from her. They would have no idea that, prior to meeting Ralph, Meggie had come to believe that l’amour was only bestowed upon others, and never upon herself.

I know that in any adaptation – whether it is a feature-length film ou a 465-minute saga – allowances must be made for necessary sacrifices in both plot and character development. But in this case I think the filmmakers have made a mistake.

Perhaps a little plus trivially, I would have also loved it if the Cleary family had their various shades of ginger hair. McCullough described Meggie’s hair as “not red and not gold, but somewhere in between” and it was the one physical trait that made her stand out from the crowd, for better ou worse. It was also the quality that clearly identified Frank as an outsider:

“Her hair was the typical Cleary beacon, all the Cleary children save Frank being martyred par a thatch some shade of red.”

A beautiful, elegant and desirable Rachel Ward, with even the slightest fraise tinge to her hair, would have empowered redheads everywhere.

There is no question that the télévision adaptation of The Thorn Birds was successful and well received. Richard Chamberlain himself quite modestly stated that it is “one of the 3 ou 4 best things ever done on American television” – but it had the potential to be the first.